By Jioni Tuck

In Negroland by Margo Jefferson, many of the struggles that Jefferson outlined had to do with the intersections of gender and race. Because Jefferson is a Black woman, she has had to deal with both racism and sexism which play off of each other. The potency of this intersection has almost always been in the rhetoric of Black women though theories about this intersection have evolved over time. The concept of Black feminism proliferated in the 1970s and 1980s though Black feminists had existed long before that time. In this blog post I will talk about the history of Black feminism and situate Jefferson’s exposure to Black feminism within that history.

In “Racism and Women’s Studies” by Barbara Smith, Smith defines feminism as “the political theory and practice that struggles to free all women: women of color, working class women, poor women, disabled women, Jewish women, lesbians, old women—as well as white, economically privileged, heterosexual women”[1]. This definition is more nuanced than most standard definitions of feminism are. When asked about feminism people usually say something similar to “equality between sexes or genders” but Smith’s definition goes the extra step to enumerate the different identities that women have and acknowledges that they also have the right to freedom. Smith presents feminism through an intersectional lens that has not been present in the mainstream feminist movement until more recently. Scholars categorize historical feminist movements into three waves. The first wave of feminism centered around suffrage in the late 1800s and early 1900s. The second wave of feminism rode on the coattails of the civil rights movement and began in the late 1960s and ended in the 1980s. The third wave feminist movement began in the late 1980s and, most argue, is still going on.

The categorization of feminism into three different waves is useful when reviewing how Black women have fit into feminist movements. For most of history, Black women have been excluded from feminist movements. Not until the late 1960s did the feminist movement become more inclusive. Black women began to take on the word “feminist” and more clearly define what feminism meant for them as Black women. I will start by giving an overview of Black women and feminism in the 1800s and early 1900s. Then I will talk about Black feminism in the 1960s and 1970s using Margo Jefferson’s experiences as a base for analysis. I will also talk about Black feminism from the 1970s to the present day.

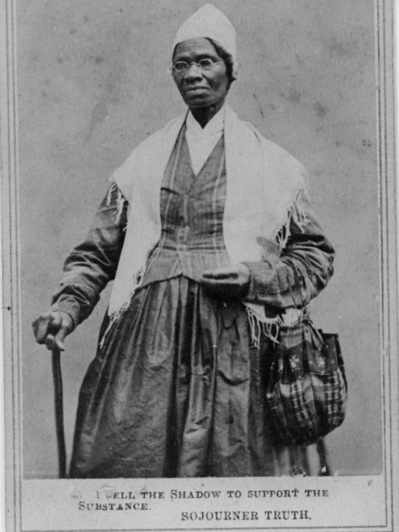

Though feminism in the Black community become more noticeable in the 1970s, Black women have always held feminist ideologies. Black women are challenged to look at the issue of gender inequality from both the perspective of a woman and the perspective of a person of color, institutionally marginalized by the United States government and society. As a result, their feminism was not always labeled feminism. In the struggle for racial equality, gender equality was often laid by the wayside and in the struggle for gender equality, race was frequently overlooked. Black women have always had to grapple with this intersection and the struggle that comes with it. Sojourner Truth’s “Ain’t I a Woman” Speech at the 1851 Women’s Convention in Akron, Ohio contrasts the oppressions faced by white and Black women. She pointed out that Black women have always been subject to racial abuse while white women were treated as delicate and emotional[2].

Leaders of the first wave feminist movement like Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony fought for the women’s right to vote but prioritized that over racial equality. For example, they did not support the 15th amendment because they did not want Black men to have the right to vote before white women. In 1904, Mary Church Terrell, one of the first African American women to earn a college degree, said that “Not only are colored women with ambition and aspiration handicapped on account of their sex, but they are almost everywhere baffled and mocked because of their race”[3] in an address called The Progress of Colored Women.

In the early 1900s, white feminists were focused on what they called universal suffrage. They wanted the United States to extend the right to vote to women. Black feminists agreed with this but they also had to deal with mass lynchings and general state violence against Black bodies. Not to mention that Black Americans legally had the right to vote but in practice were systematically barred from voting through poll taxes, literacy tests, and the addition of a grandfather clause. Despite this, Black women did not discount the importance of the 19th amendment, in 1910 Ida B. Wells-Barnett wrote that “The Negro has been given separate and inferior schools, because he has no ballot”[4]. Despite efforts made by Black feminists, there has always been a divide between the feminist movement and movements that aimed to advance Black rights.

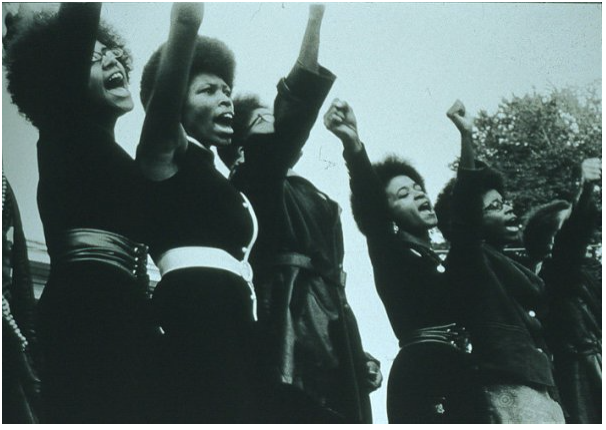

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, we see an explosion of discussion and literature that focused on what it meant to be Black and to be a woman. This was spurred in part by the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s and also by the second wave feminist movement that began in the early 1970s. Women were very involved in the Civil Rights movement, especially in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). In the summer of 1960, Ella Baker, the interim director for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), organized college students into the SNCC[5]. SNCC organized sit-ins, freedom rides, and other direct action to expose racial segregation. Within SNCC African American women were given a backseat role. Sarah Evans, a member of SNCC reported that the women in SNCC “received their share of beatings and incarcerations, but back at the headquarters…they still…did the housework; in the offices they typed, and when the media sought a public spokesperson they took a back seat”[6]. In 1964, women in SNCC wrote the SNCC Position Paper (Women in the Movement) that provided eleven examples of sexual discrimination in SNCC and asserted that “the woman in SNCC is often I the same position as that token Negro hired in a corporation”[7]. As a result of this treatment, many White Women transferred their participation to Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). Black women in SNCC “clearly had issues with male chauvinism, they could not abandon the civil rights struggle”[8] as white women did. The treatment that women faced at SNCC highlights one of the many problems that Black women faced, sexism within Black communities.

Around the same time, the National Organization for Women (NOW) was created by Betty Friedan and other influential women including two black women, Aileen Hernandez and Pauli Murray. In The Feminine Mystique by Betty Friedan, published in 1963, Friedan discussed the feeling of emptiness and unfulfillment that many white women experienced in their domestic lives at this time. While white women struggled with the cult of domesticity, Black women still faced systemic racial discrimination. Friedan’s book characterizes a difference in the struggles that Black women and white women faced in the 1960s. The second wave feminist movement, led primarily by white women, strove for gender and to some extent racial equality but given the lack of diversity in their organizations, ended up creating organizations that addressed their needs as professional, upper-middle class, white women[9]. As a result, the voices and concerns of non-white and lower class women were pushed to the wayside. Black women were pushed out of the second wave feminist movement and pulled into the Black Power movement. Even when Black women supported the demands of the feminist movement, they still had an obligation to participate in the movement against racism. Neither movement, feminist or anti-racist, fully addressed the issues that affected black women specifically.

In Negroland by Margo Jefferson, Jefferson talked about her experiences with feminism in the 1960s and 1970s. She explained how the women’s movement was controversial in Black communities since many men (and women) denounced feminism as something only for white women. People in Black communities saw feminism as an assertion of white privilege since white women were “competing…for the limited share of benefits white men had just begun to grant non-whites”[10]. Jefferson pointed out that relations between white and Black women had historically been strained and at times exploitative and that alliances between the two groups did not have a successful track record. This sentiment mirrors the struggle that Black women faced in reconciling gender based discrimination with race based discrimination. Jefferson highlighted the fact that women of color are regularly discriminated against based on their race and based on their gender and that organizations designed to address the singular identities did not do enough to address the problems that Black women specifically faced.

She also pointed to the way that Black communities often label certain social issues as being “only for white people”. In Jefferson’s experience, Black people labeled feminism as being for white people. This discounted the fact that gender equality impacts Black women and also ignores mental illness in Black communities. After acknowledging the disconnect that many Black people felt from the feminist movement, she wrote that many Black women were eager to learn more about Black feminist thought and join organizations centered on Black feminism.

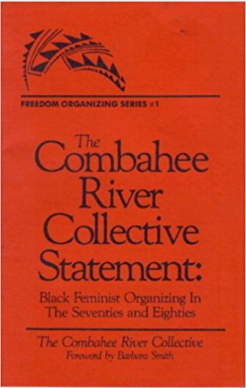

The 1970s and 1980s saw an increase in literature and organization focusing on feminism as it related to Black women and women of color more generally. Prominent scholars at this time were Alice Walker, Angela Davis, and bell hooks. Organizations like the Combahee River Coalition, the National Black Feminist Organization, and the Salsa Soul Sisters addressed feminist issues through the lens of women of color[11]. Based on the activism done in both racial justice and gender equality movements, Black scholars and activists began to talk about intersections between racial and gender equality movements. The Combahee River Collective is a prime example of this. In 1974, the Combahee River Collective, a group of Black, lesbian, feminists wrote The Combahee River Collective Statement that stated their belief that “sexual politics under patriarchy is as pervasive in Black women’s lives as are the politics of class and race”[12]. They emphasized the intersection between race, class, and sex when talking about oppression. In Black Women’s Manifesto; Double Jeopardy: To Be Black and Female by Frances M. Beal, published in 1969, Beal highlighted the racialized nature of the gender-wage gap and pointed out differences between white women’s liberation movements and racial equality movements. In Ain’t I a Woman?: Black women and feminism by bell hooks, hooks argued that racism and sexism during slavery resulted in black women being the most marginalized group in American society and that stereotypes and prejudices articulated during slavery still affect Black women today. Most Black women used the term “Black feminism”, but some, like Alice Walker, chose to reject the term “feminism” or “feminist” and create a different term. Alice Walker created the term “Womanist” to describe “A black feminist or feminist of color”[13] (In Search of Our Mother’s Gardens: Womanist Prose). Using social justice movements as a basis, in the 1970s, Black women began to theorize and vocalize more concrete conceptions of women’s equality as it related to Black women specifically.

Black women have always been doubly discriminated against because of their race and gender. Black feminists have always existed though the 1970s and 1980s saw a proliferation in literature and analysis of Black feminism. In Negroland, Jefferson touched on one of many barriers that Black women faced in fighting for their rights, the belief that feminism is for white women. Given the history of feminism, this thought process is not completely wrong, though it is more nuanced that many Black people with this belief make it out to be. Through situating Jefferson’s experiences with Black feminism into a brief history of the relationship between Black women and feminism, I hoped to give a more holistic view of the topic of Black feminism.

Works Cited

[1] Smith, Barbara, Patricia Bell Scott, and Gloria T Hull. All the Women Are White, All the Blacks Are Men, but Some of Us Are Brave: Black Women’s Studies. Old Westbury, N.Y.: Feminist Press, 1982. Pg. 25

[2] Smith, Sharon. “Black Feminism and Intersectionality.” Black Feminism and Intersectionality | International Socialist Review. N.p., n.d. Web.

[3] Smith, Barbara, Patricia Bell Scott, and Gloria T Hull. All the Women Are White, All the Blacks Are Men, but Some of Us Are Brave: Black Women’s Studies. Old Westbury, N.Y.: Feminist Press, 1982. Pg. 40

[4] Taylor, Ula. “The Historical Evolution of Black Feminist Theory and Praxis.” Journal of Black Studies 29.2 (1998): 234-53. Web.

[5] Ibid

[6] Ibid Pg. 240

[7] King, Mary, Casey Hayden, and Elaine Delott Baker. “SNCC Position Paper.” (n.d.): n. pag. Web.

[8] Taylor, Ula. “The Historical Evolution of Black Feminist Theory and Praxis.” Journal of Black Studies 29.2 (1998): 234-53. Web. Pg. 241

[9] Taylor, Ula. “The Historical Evolution of Black Feminist Theory and Praxis.” Journal of Black Studies 29.2 (1998): 234-53. Web.

[10] Jefferson, Margo. Negroland. Place of Publication Not Identified: Granta, 2017. Print.

Pg. 170

[11] Taylor, Ula. “The Historical Evolution of Black Feminist Theory and Praxis.” Journal of Black Studies 29.2 (1998): 234-53. Web.

[12] Combine River Collective. “Combine River Collective Statement.” The Combahee River Collective Statement. N.p., n.d. Web. Pg. 32

[13] Walker, Alice. In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens: Womanist Prose. Place of Publication Not Identified: Betascript, 2011. Print.

Bibliography:

Hooks, Bell, and Rosa Bell. Ain’t I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism. London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2015. Print.

Beal, Frances. Double Jeopardy: To Be Black and Female. Detroit, MI: Radical Education Project, 1971. Print.

Images:

- Foster, Kimberly. “Black Feminist Contradictions: We All Got ‘Em.” Celebrating the Fullness of Black Womanhood. For Harriet, 13 Feb. 2012. Web.

- “Sojourner Truth.” National Parks Service. U.S. Department of the Interior, n.d. Web.

- “Black Feminism: A Short Intro.” Decolonize ALL The Things. Decolonize All The Things, 19 June 2015. Web.

- “S.N.C.C.” Documentary Of… N.p., n.d. Web.

- Combahee River Collective (Author). “Combabee River Collective Statement: Black Feminist Organizations in the 70s and 80s First Edition Edition.” Combabee River Collective Statement: Black Feminist Organizations in the 70s and 80s. Amazon.com: Books. N.p., n.d. Web.

Excellently written

LikeLike